We begin this episode on May 8th, 1968 at the Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum. Catfish Hunter was pitching for the A’s and Al Helfer, so called Mr. Baseball Radio, was about to broadcast history on KNBR in San Francisco.

“Fastball on the inside corner. Hunter has pitched a no hitter!” Helfer screamed into the mic. “Jim ‘Catfish’ Hunter didn’t allow a man to get to first base against the Minnesota Twins. You can well imagine how this young man feels,” he told the audience.

I strongly suspect Catfish was elated. He was not quite 22 years old, and he had just pitched the first perfect game in the American League in 46 years. I also suspect fans in Oakland were thrilled—a perfect game the first year the franchise was there.

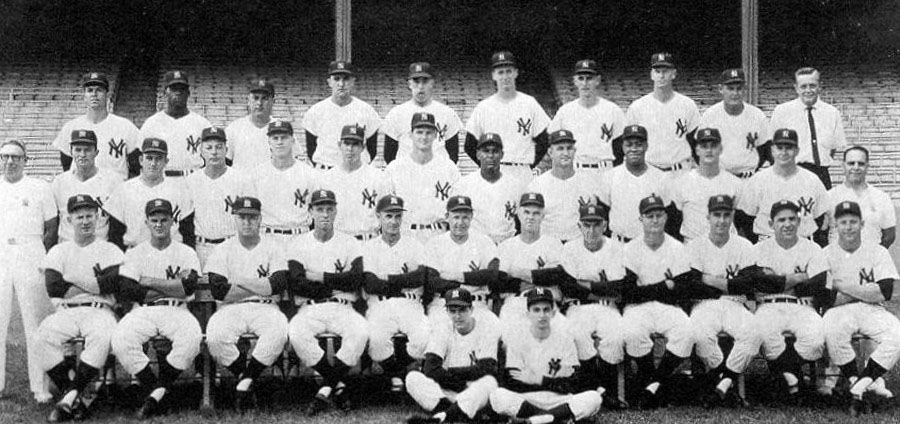

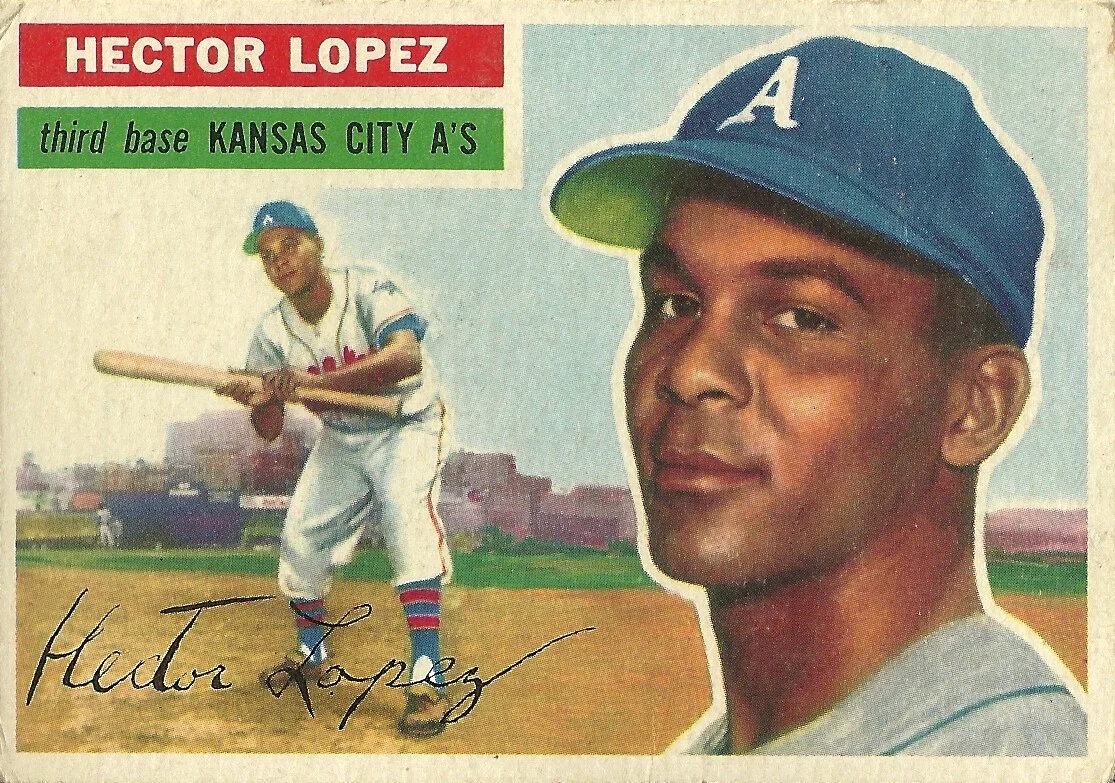

But for 12 year old me, and for many baseball fans in Kansas City, this was just another what-could-have-been moment. You see, this perfect game was a preview of an Oakland dynasty, a team that would win three consecutive World Series with players who started their careers in Kansas City

Just a year before Catfish’s gem, Kansas City was fighting to keep the A’s. But, it turns out, the fix was in and K.C. baseball fans were going to get drilled by a Charlie Finley fastball.

“A Dream Come True. It’s Oakland A’s Now,” said the big headline on the front of the San Francisco Examiner sports page on October 19th, 1967.

The day before, American League owners approved Charlie Finley’s request to move the A’s from Kansas City to Oakland. Literally from the moment Finley bought the club and came to town in 1960, he wanted to move the A’s. He claimed otherwise but it was a lie.

“I think Finley was very disappointed and thought Kansas City was not a good baseball town and immediately that first season began to wonder if he should move the team to another city,” says author John Peterson who wrote a great history of the team simply called The Kansas City Athletics. “One of the cities he looked at was Dallas. Supposedly, he went down there and brought back hats to manager Hank Bauer and wanted the players to wear Dallas hats. He also scouted out the Cotton Bowl to see if that would be a suitable site for baseball.”

Finley considered Seattle, and asked the American League to let him move to Louisville but he was the only owner to vote yes on that. But after years of agitating, demanding and plain old kvetching, his fellow owners had enough and voted to let Finley move.

So many people in the area tried like hell to keep the team in Kansas City, including former Kansas City Councilman Sal Capra.

“You asked about in the lease with Charlie Finley, there was a provision that we had to draw 800,000 people and when he start acting up like he did, the attendance was going down so business leaders and the (Kansas City) Star and others came along the last three or four weeks and bought the tickets so that we complied with the 800,000 people,” Capra remembers.

It was a drip, drip, drip of pain and anxiety for A’s fans in 1967. Will they stay or will they go? “Oakland Offer Tempts Finley” the headline read on the front page of the morning Kansas City Times on July 21st, the same day the team started a weekend homestead against the White Sox.

“I’m very much impressed,” Finley told the AP.

In fact, he had already made up his mind. He was chopping at the bit. He thought he was going to be the next Major League West Coast success. He was going to follow in the footsteps of the Dodgers in Los Angles and the Giants in San Fransisco who moved west from New York after seeing how well the A’s fared in Kansas City after fleeing Philadelphia.

Kansas City tried everything, including passing a $102 million bond issue to build the Truman Sports Complex. Even a brand new baseball only stadium couldn’t convince Finley to stay. He had badgered American League owners so much, they finally said yes at the next league meeting.

W.A. Clarkson was chair of the Jackson County Sports Authority at the time and was part of the team at the league meeting in Chicago’s Drake Hotel. The Kansas City group got the official word from American League President Joe Cronin. The fix was in for the A’s to move to Oakland, everyone in the baseball world knew that. But Major League Baseball was going to expand and Kansas City was waiting to hear about that.

“The thing that was most upsetting was that they would not give any specifics about an expansion team to replace the A’s in Kansas City,” Clarkson recalled. “They (MLB) indicated that we would be given consideration and then, to put it candidly, all hell broke loose from our perspective. I remember Ike Davis, the mayor who normally was very straight forward, very lawyerly, and he exploded. And I remember Senator Symington got so mad he stormed out of the room.”

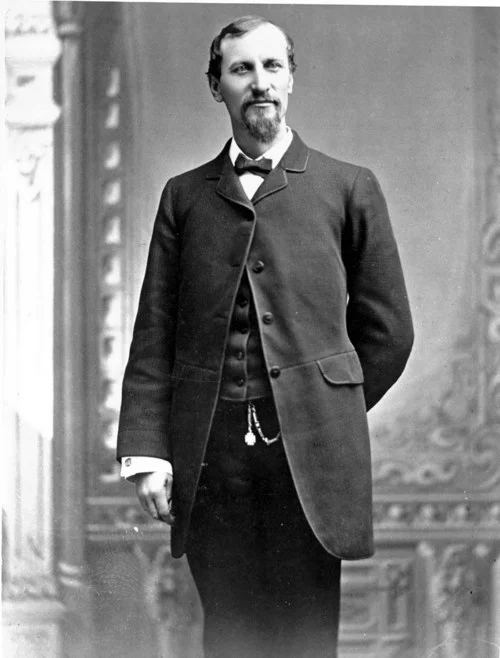

Turns out that Missouri Sen. Stu Symington wasn’t a guy you wanted to piss off. Stuart Symington was the first Air Force Secretary, successfully leading the Berlin Airlift. He was a powerful member of the Senate Armed Services and Foreign Affairs committees. And he hated Senator Joe McCarthy.

They argued and sniped at each other during the Army-McCarthy hearings in the spring of 1954. Not many people were willing to take on Joe McCarthy. Symington was. So facing down baseball team owners 13 years later, not such a big deal Clarkson remembers the KC representatives reconvening, and Sen. Symington calling Yankee president Mike Burke.

Symington told him that if Kansas City didn’t get a team for the 1969 season, major league baseball could say goodbye to its antitrust exemption.

“And then there was frantic bit of activity on the part of the American League group. They reconvened their meeting and got back to us late that evening and the word came down that yes, the A’s were going to be allowed to move, there would be a one year hiatus for the 1968 season, and Kansas City would be granted an expansion league franchise for the 1969 season. That’s when Ewing Kauffman got the franchise for what would then become the Kansas City Royals. That was in 1968 and they opened the season in 1969,” says Clarkson.

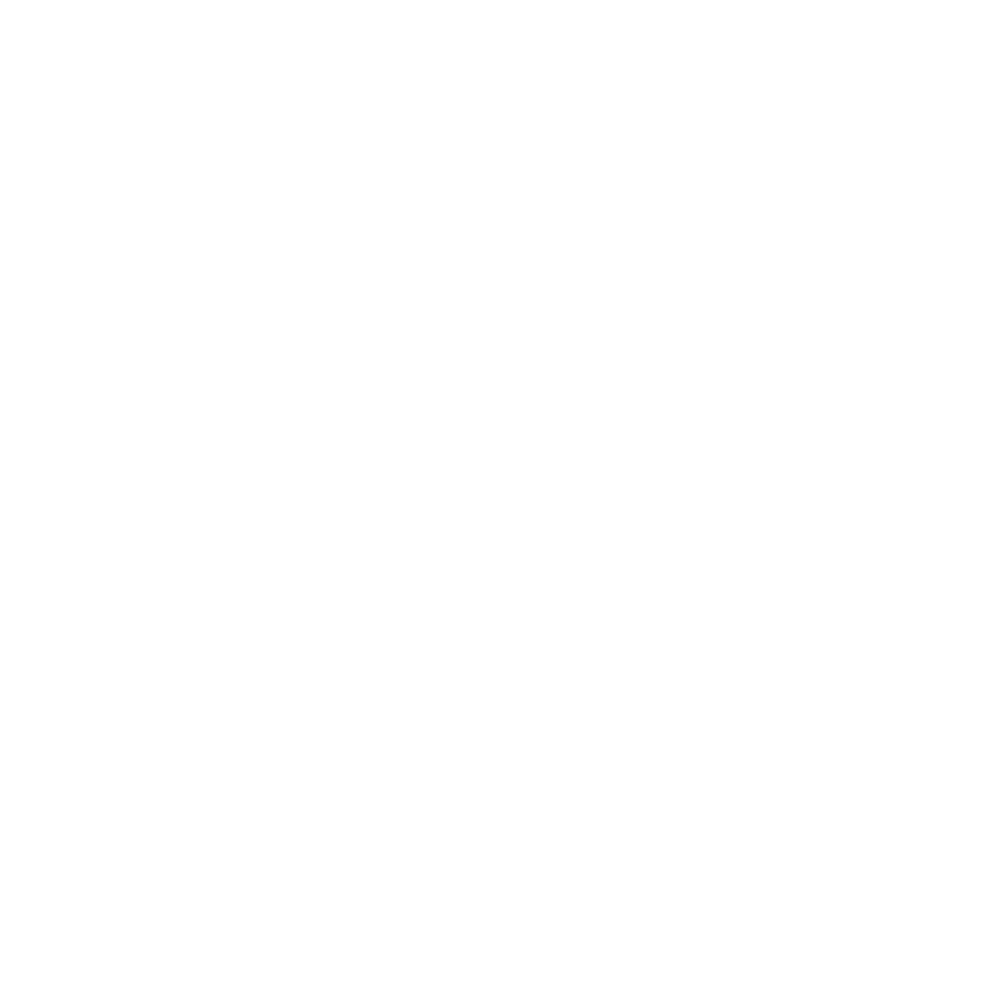

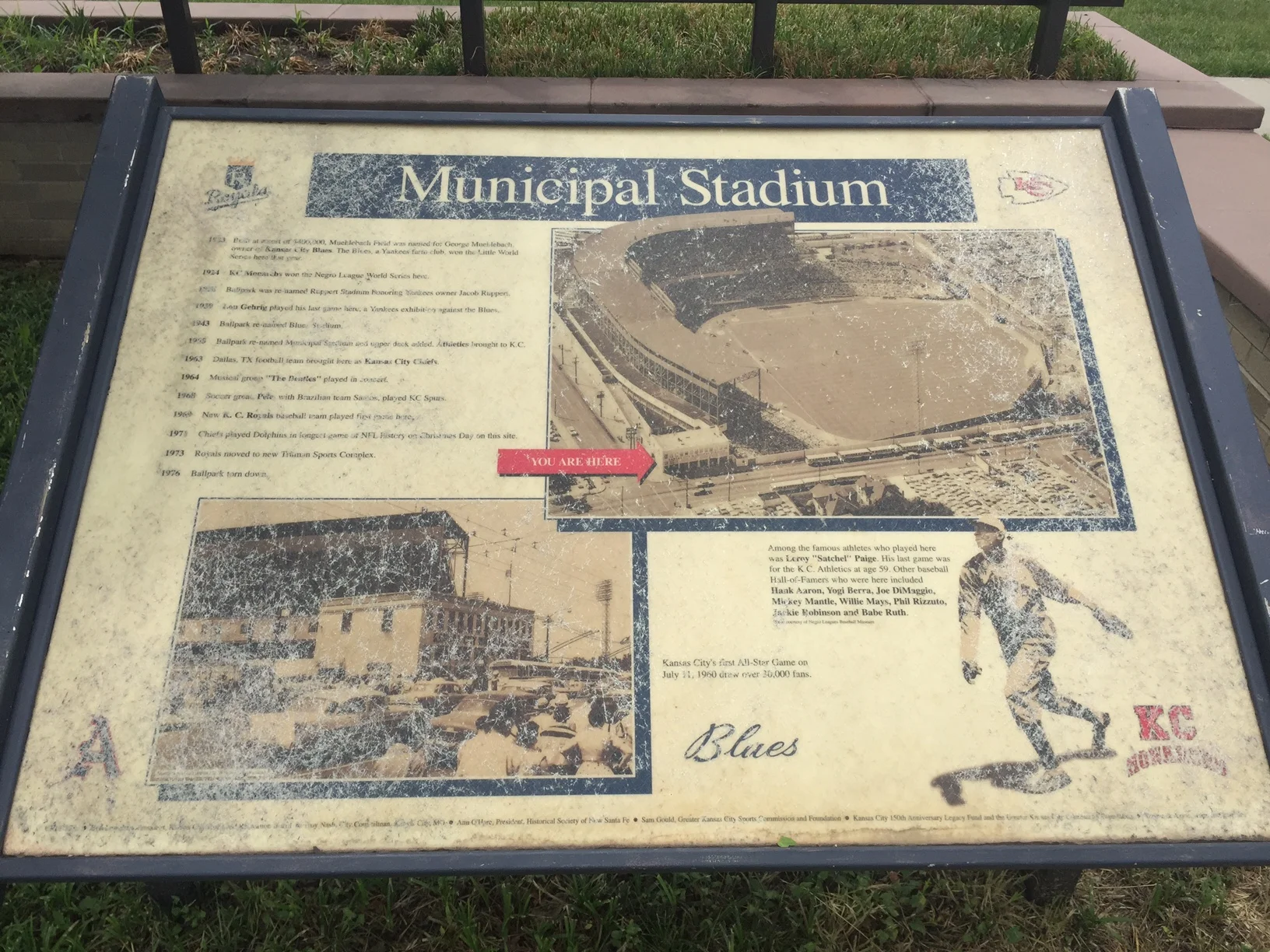

The Royals opened the season at 22nd and Brooklyn Avenue, the same place the A’s played when they arrived in 1954. I was at that opening game with a whole new team of players to root for. The Royals beat the Twins in extra innings, Joe Keough singled in Joe Foy in the 12th. Lou Piniella went four-for-five. He would go on to be the American League rookie of the year. The win would go to Moe Drabowski in relief. He was one of four Royals who also played for the A’s in Kansas City.

In the 50 years the A’s have been in Oakland they’ve won four World Series, including an amazing three in a row from 1972 to 1974 and six American League Pennants. In those same 50 years, the Royals have two World Championships and four American League Pennants. Baseball people would probably disagree, but I’m going to call it even, mostly because I love Kansas City but also because it’s my podcast.

This season of Archiver was produced by Matt Hodapp and Linda Haskins. Archiver is produced with Do Good Productions, where Nancy Seelen is executive producer and with the Center for Midwestern Studies where Diane Muti Burke is Director.

Two special thank yous as we wrap this season. First to Jeff Logan from the Kansas City Baseball Historical Society who provided not just his deep knowledge of Kansas City sports but the cool radio clips you heard. And to Mitch Nathanson who was our Philadelphia A’s expert. I just finished his biography of the slugger Dick Allen called “God Almighty Hisself” and it is terrific.

If you missed any of our Archiver episodes make sure to subscribe to the podcast on iTunes or where ever you get your podcasts.