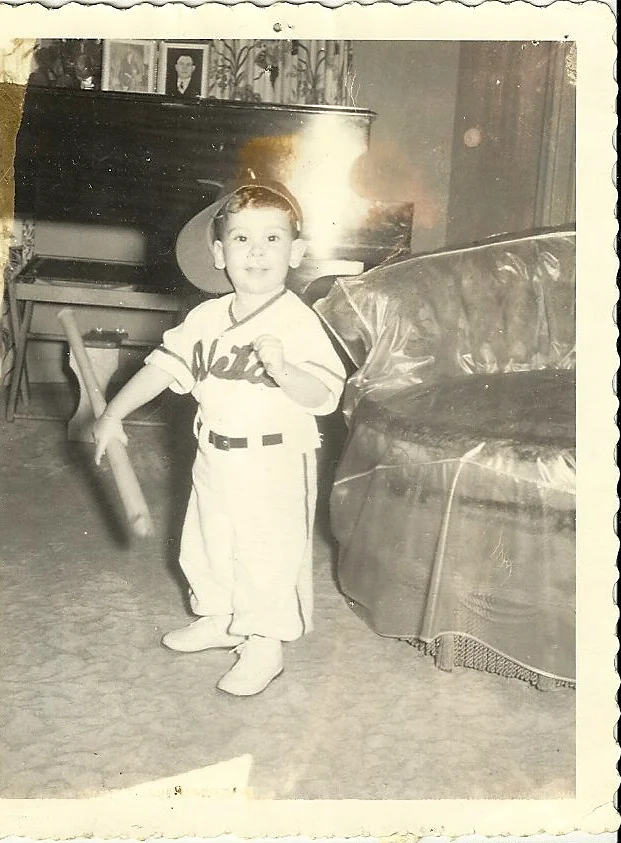

I've always loved baseball. In fact here's a picture of me as a little kid just to prove it! And, as you can see, my love began with the Kansas City Athletics. To tell the story of how that team came to be in my hometown, we have to go back to the 50s.

It’s the beginning of 1955. The Kansas City Athletics, known as the A’s, are kicking off their first year in Kansas City after leaving Philadelphia where they played since 1901.

On the surface, it all looked so good; a big league team was in town for the first time, an updated Municipal Stadium, fans streaming into the ball park. But if you peeked underneath, it was all built on sleazy backroom business deals and one-sided trades all orchestrated by the hated New York Yankees and their hand-picked A’s owner.

“It was no secret that this was an unholy alliance,” says author Mitch Nathanson who has written extensively about sports in Philadelphia. "The other club owners pointed this out in advance. It was written about in newspapers that this is not going to be a sale to an independent entity. This is going to someone who was essentially a cousin of the Yankees.”

It was one of the greatest conspiracies in sports history. One that would lead to turmoil in Kansas City, a congressional hearing and, eventually, one of the craziest owners in all of professional sports.

To tell the story of the Kansas City Athletics, you have to start in Philadelphia where they were a charter member of the new American League.

The first thing the A’s did was hire a former catcher named Cornelius McGillicuddy to manage the club. Although from the time he was a boy in Massachusetts, he was called Connie Mack.

Starting in 1886, Mack spent 11 seasons in the major leagues and a few more in the minors before being hired on by the A’s. He also bought a 25 percent share of the team and later the Mack family would own the club outright.

As they do to this day, baseball managers wear the team’s uniform. Not Mack, he always wore a suit and often a straw hat.

It’s hard now to think of Philadelphia as anything but a Phillies town, but for the first half of the 20th century baseball there was dominated by the A’s. They were World Series champs in 1910, ‘11 and ‘13. They went through lean times and roared back in the ‘20s and ‘30s when they were world champs in 1929 and 1930.

“For the 54 years that the A’s and the Phillies played together in Philadelphia, the A’s out drew the Phillies. I think 40 times, so there were only a few years where the Phillies ever out drew the A's,” says Nathanson, who is also a law professor at Villanova University.

“Unlike in Chicago where you would be a Cubs fan or a White Sox fan, or in New York where you would be a Giants fan, but not a Dodger's fan, that wasn’t the case in Philadelphia. There were people who were A’s fans who didn't hate the Phillies. There was nothing to hate. They were just innocuous. They were invisible almost. It was a different situation in Philadelphia than it was in these other towns where there are rivalries between the teams. There were no rivalries between the Phillies and the A's. The Phillies were an afterthought. The A’s were the team that people followed.”

So, led by Mack, the A’s and their fans enjoyed a couple of dynasties and successes at the box office. Mack eventually owned the team and Shibe Park and ran the whole operation. But after World War II, the A’s were awful. In 1946, 1947, and, well, to be honest they were awful for the rest of their time in Philadelphia.

Mack was now in his 80s and his mind was shot. He would call out for players who played for him decades ago. He brought his inept sons Earl and Roy into top jobs in the organization. Those two were battling Connie Mack, Jr., Mack’s son from his first marriage, over the future of the franchise.

American League owners were worried. Puny crowds meant less of a take for teams visiting Philadelphia. They wanted the A’s out of Philadelphia. So the hated New York Yankees hatched a scheme that would enrich the team both on and off the field. But first, to make their plan work they had to get the A’s to Kansas City.

In Octorber 1954, American League President Will Harridge introduced a man named Arnold Johnson as the new owner of the A’s. Newsreel footage showed an odd looking news conference; Harridge was sitting in a chair and Johnson was sitting on the arm rest, his arm around the American League President’s shoulder. But getting to this point was a constant drama with confussion mixed in.

First, Johnson had a long business relationship with Yankees’ owners, Dan Topping and Dell Webb. The Yankees already had a foot print in Kansas City. Their top minor league team, the Blues, had been playing there for decades. In fact, Johnson bought the stadium at 22nd and Brooklyn from Topping and Webb.

“Johnson pretty much owns everything he has to Topping and Webb,” says Nathanson. “In addition if they move to Kansas City, the stadium has to be refurbished and Del Webb's construction company is going to handle the construction. So there's money that goes directly into Del Webb's pocket and they know that Johnson is the guy they can control. The Yankees were successful for 40 years and you could say they were a great organization, but they were great because they were taking players from other clubs to maintain their dynasty,” he says.

As this was all happening most of the league was pulling its hair out as the Mack family fought over whether to sell the club to Johnson, find a way to keep it in the family, or sell the A’s to buyers in Philadelphia.

In fact, Roy Mack, the son appointed by Connie to run the club, had made a deal with local businessmen to buy the A’s and keep them in Philadelphia and American League owners had already approved that deal.

But Johnson wasn’t going to let that happen. “He took a plane directly to Philadelphia, drove straight to Roy’s house, marched in and made him a deal he couldn’t refuse,” says Bob Worthington with the Philadelphia A’s Historical Society.

He offered more money for Roy’s shares in the club and a juicy job in the front office in Kansas City.

“So, Roy decided to switch his loyalties back to Arnold Johnson and to make the deal with Johnson,” says Worthington. “Now that created all kinds of problems, two in particular. Number one, the agreement with the Philadelphia syndicate had already been signed. That was the deal that was on the table and that was the deal that was going to be considered at the next American League ownership meeting in late October. When Roy Mack had signed that agreement along with his father Connie and his brother Earl, they had telegraphed William Herridge and said, we have concluded this deal."

“The second issue, of course, was Roy had agreed to transfer his loyalty back to Arnold Johnson, accept that deal, but Connie and Earl hadn’t. So, Roy confronted a significant situation, a problematic situation that he had to deal with. The saving grace for Roy Mack was that the deal with the Philadelphia syndicate was subject to approval by the American League to agree to that agreement, to accept it, to condone it, to approve it so that Roy Mack and his father and brother could sell the stock to the Philadelphia syndicate. When they showed up at the ownership meeting in late October, this would have been October 28th, all the American League owners walked into the room assuming they were simply going to vote on the deal for the Philadelphia syndicate, transfer ownership of the Athletics to that group, the Athletics would stay in Philadelphia and be done with it. But, to the amazment of the other owners, when it came time to vote, Roy Mack voted against his own deal."

Those businessmen of the Philadelphia syndicate were outside the room just waiting to hear that, yes, they were the new owners of the A’s. “The Philadelphia syndicate group was really angry,” Worthington continues. “They suspected a double cross, that somehow, someone, one of the Macks had walked away from the deal they had only signed days earlier and, indeed, that was the case.”

Finally, the deal was done. Hearts soared in Kansas City where business leaders and politicians had been working for months to lure the team from Philadelphia, perhaps not aware of just how much of a role the Yankees played and the scheme they were ready to hatch.

By December, the downtown Macy’s was advertising Kansas City A’s ties for two dollars. “K.C. Athletics blazes forth in pink. He’ll wear it with pride,” the ad in the Kansas City Times raved. And pride in the city’s brand new big league team...off the darn charts.

“And when they did come into Kansas City, they were flying into the downtown airport. They see so many people celebrating that they made the plane circle the city several times just to see how excited the fans were in Kansas City for them to be here,” according to Jeff Logan, who is president of the Kansas City Baseball Historical Society.

That’s in our next installment of Archiver: The A’s in Kansas City.

Music used in this episode Rally, The Big Ten, The Silver Hatch and In Passage by Blue Dot Sessions