When you think about black major league baseball players—those who led the way in breaking the color barrier—you think Jackie Robinson of course.

They even wrote a swing tune about Jakcie called “Did You See Jackie Robinson Hit that Ball” performed by Buddy Johnson and his Orchestra in 1949. It reached number 13 on the charts that year.

Jackie spent part of the 1945 season with the Negro League Kansas City Monarchs before moving on to the Dodger organization. And while we all know the Monarch's place in baseball history—they won ten league championships and launched the big league careers of many black players–you might not know the role the A’s played in integrating blacks into the big leagues.

“It was of the utmost importance to us as a city, we were progressive enough to have a team that included everybody,” says Jeff Logan, president of the Kansas City Baseball Historical Society. “I think that cities like Boston are still branded in that fashion, that they are a little racist and I don't think Kansas City has that tag.”

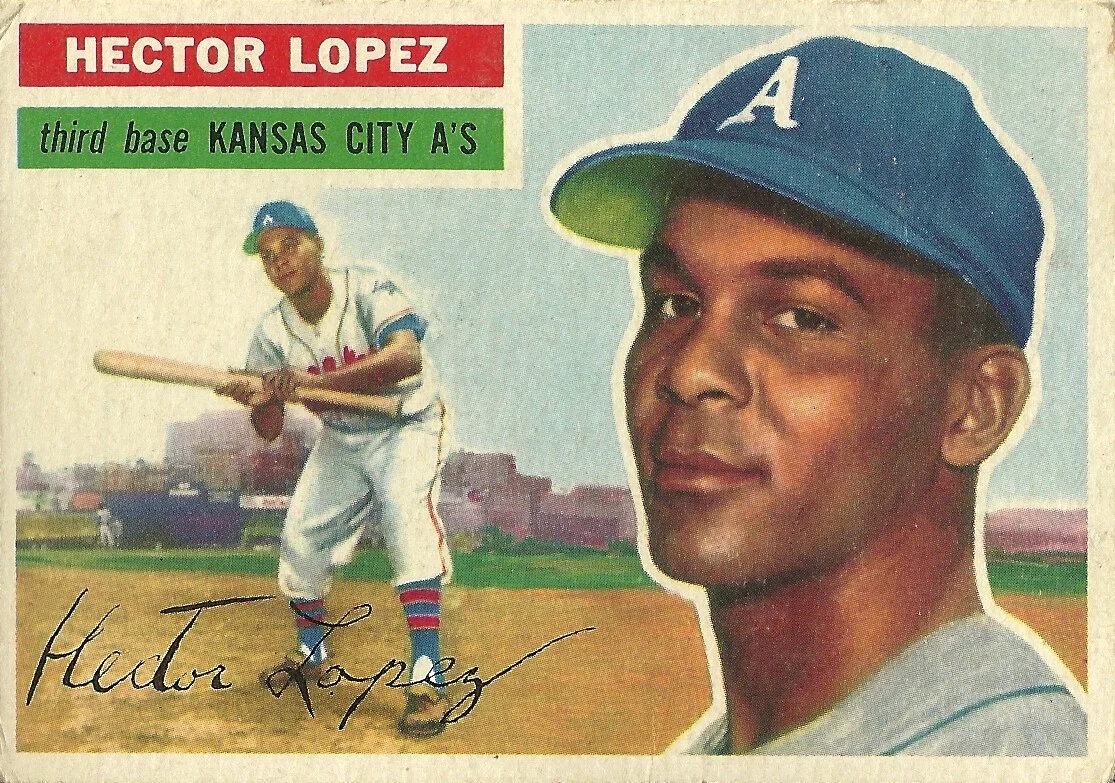

If you look at that the first team photo of the Kansas City A’s in 1955, for the most part it looks like you’d expect for the time, baggy uniforms worn by men who look more like regular guys than professional athletes. But, when you look a little closer, there’s something different from most teams at the time...there are three black players: Hector Lopez, Harry ‘Suitcase’ Simpson and the controsersial Vic Power.

“The Kansas City A's embraced these players simply because they were good enough and probably better than a lot of the other players. They (the A’s) wanted to win. Let's face it, if you are not going to integrate the best players in the sport then you're not trying to win,”

Just how good were the black players on those early A’s teams? That was obvious at the 1956 All-Star Game at Griffith Stadium in Washington D.C.

Simpson and Power were the only black players on the American League roster that year. The National League, which embraced integration much earlier than the American League, had six black players including Hank Aaron and Willie Mays.

The morning after the game, the Kansas City Times gave Simpson and Power just two paragraphs on a full page of all-star coverage—not a hint that the A’s provided the only two black players on the A.L. roster.

“Power played three innings at first base but handled only routine chances,” A’s beat reporter Joe McGuff wrote. “Harry Simpson, the only other Kansas City player on the All-Star squad, pinch hit for Billy Pierce in the third and struck out on three pitches.”

Reading the paper in 1956, that amount of coverage would probably seem right. But 60 years later, when I found that clip, it felt odd to me.

Harry Simpson played for five big league clubs but that’s not why his nickname was suitcase. He picked that up playing in the Negro Leagues because, it was said, his shoes were as big as suitcases.

Hector Lopez was the third black player on those early Kansas City teams. He grew up in the Panama Canal Zone and played most of his career with the Yankees.

I should note that Latino players made their mark in both the major leagues and Nego Leagues. Most early Hispanic players were Cuban, many historians believe baseball spread quickly on the island when the U.S. occupied it after the Spanish American War.

Also, the number of Hispanic players in the majors began to increase in 1947, the year Jackie broke the color barrier. But back to Power and why he was controversial.

“Vic Power played here with the Blues. Power would have gone to the Yankees but Power had a girlfriend who was a mulatta and he had a red convertible and he’d ride in that convertible with this girl, and she was pretty and her hair was blowing. They thought she was a white girl,” according to Buck O’Niell the legendary Monarchs manager. “That’s one of the reasons Elston Howard was the first black Yankee instead of Vic Power.”

Power was from Puerto Rico, and when he was home he went by his real name, Victor Pellot. Being from Puerto Rico he wasn’t used to segregation, Jim Crow or the social mores blacks had to endure. Power was talented and flashy. In the 1950s, it was fine for black players to be talented but flashy could get you in trouble.

“I just loved to watch him. He made the greatest play I’ve ever seen in the history of baseball for me,” says Chuck Dobson, a Kansas City native who played ball at the University of Kansas before signing with the A’s in 1966. He watched Power play at Municipal Stadium.

“He made the greatest play I’ve ever seen right here. Jumped over a park bench, his back turned to the infield, cocked the ball like this with his back to the infield, he’s in midair over a park bench” and fired the ball back into the infield.

Dobson also says Power was an intimidating hitter. “Power would stand like this and he’d take that bat and he’d point it at the pitcher, point it right at the pitcher, and he’d swing that thing.”

There’s a story about Power in the Roberto Clemente biography by author David Maraniss. Power, Maraniss writes, walks into a segregated restaurant where he’s promptly told by the waitress that she didn’t serve Negros. That’s fine, Power told her, he didn’t eat them.

One of my favorite A’s in the early 60s was pitcher Johnny Wyatt. In 1961, Wyatt broke in with the A’s after getting his start with the Indianapolis Clowns in the Negro Leagues. There was a time, believe it or not, when people thought that African Americans weren't equipped to be starting pitchers. “That seemed to be the case with the playing quarterback too”, says Logan. “I think we found out that's probably not true since there's so many great quarterbacks.”

Jeff Logan says playing in Municipal Stadium meant a lot to black fans.

“The Kansas City A’s played at 22nd and Brooklyn in Municipal Stadium in the heart or the urban core. A lot of the people in that area were African American and those people were drawn to baseball. I think the worst thing that ever happened in sports history is when we built a stadium out in a field in the middle of nowhere. I think that's led to a lot of things. We don't have many African Americans playing baseball now. I wish the stadium was still there.”

Alas, it is not. But it’s lovingly remembered by everyone from former players to Beattles fans. 22nd and Brooklyn Avenue. That’s our next installment of Archiver, The A’s in Kansas City.

Music used in this episode: Cat's Eye, Rally, and The Summit by Blue Dot Sessions