In 1936 the federal government released a film. They called it a documentary, but it was mostly propaganda. Many would argue that its cause was noble rather than sinister. Others, as we’ll see, would vehemently disagree. But to understand why the federal government got into the propaganda film business, you first need to understand the Dust Bowl.

To understand what life was like for Kansans who lived through the Dust Bowl, we searched deep into the oral history collection at the Kansas Historical Society. These are excerpts of recordings we found from people who lived during that time:

"Tell you a little bit about the dust storms. They did not blow in. There was no wind. It was quite as could be, still."

"By the time it (dust storm) got over as far as our place, we couldn't see the neighbors we couldn't see our own front porch light. It was frightening. You thought at first that you'd gotten in on the last day in the world."

"Our youngest child was only about two years old, and at night I would wet one of the crib sheets and put it over the crib so he could breathe."

"It was rough but we learned to accept our lot in life and look for better times."

As you can see, life was rough for everyone during the Dust Bowl. The Department of Agriculture decided much of the Dust Bowl was the fault of bad farming practices, and it wanted them stopped. To do that, they needed farmers to buy into new programs and need congress to fund them.

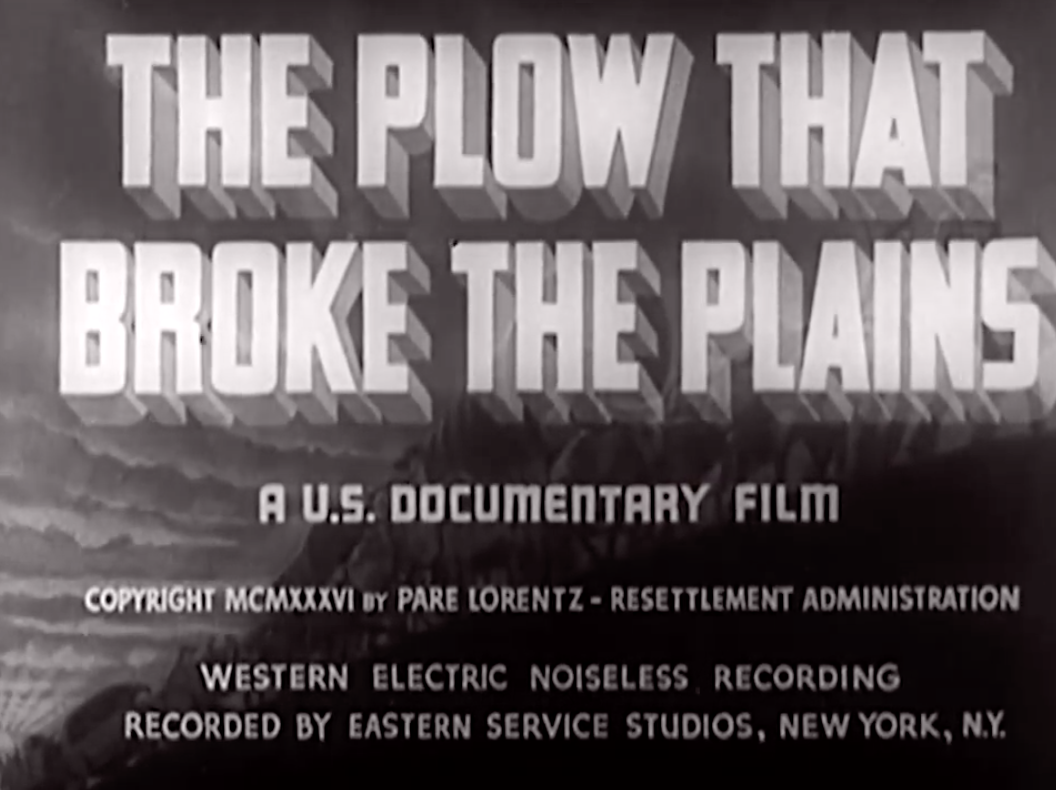

And that’s where our film comes in. It was called "The Plow That Broke The Plains". While paid for by the federal government it was the brainchild of first time director Pare Lorentz.

Parts of it were shot in Kansas and the lush score, as much a character in the film as the land, was composed by Virgil Thompson who was born in Kansas City.

Film was becoming the most powerful media of the time, and Washington was going to use it to change hearts and minds. The government wanted to show that there are good ways to use the land and bad ways.

The film shows cattle and cowboys using the vast grasslands of the plains to raise beef. But suddenly the music changes, the visuals go from the natural beauty of the plains to farmers cultivating it. You see plows breaking the plains. It’s ominous.

The swath of the Great Plains that stretched from Canada to the Rio Grande was super productive for many years. There were several years of record rainfall early in the century, and because farmers used mules rather than tractors to plow, the land used for wheat was somewhat limited.

But then the assassination of the Archduke Ferdinand in Sarajevo changed farming in Kansas.

England declares war in Germany, Belgium Invaded screams the fake headline in the film. And then the headline changes to: "War News Tumbles Securities, Stock Exchange Closed, Wheat Prices Soar. Plow To The Fence For National Defense".

Now the movie shows tractors in formation plowing the plains. If they look like tanks entering battle, well, so much the better. In fact, at one point tanks and tractors are intercut. War, of course, needs soldiers and soldiers must be fed so the governmentwas buying everything in sight.

After the allies win the war land speculators encourage some of the returning doughboys and others to move to the plains and put even more land into production. Then the stock market crashed in 1929. And in short order wheat prices plunged from $25 a bushel in 1929 to just 39 cents in 1932.

There’s a confluence of events in the early 30s that lead to the production of "The Plow that Broke the Plains". Land was being over-farmed. Much of that land should have never been plowed. The rain stops. And Franklin Roosevelt is in the White House. FDR creates something called the Resettlement Administration in 1935. Its mission was to move farmers off marginal land in the Dust Bowl region and help them move to other parts of the country. The government made this film to sell its plan to congress and voters. It would make many other movies during the depression but this was the first and it just didn’t sit well with many in Kansas.

William Lindsey White, son of William Allen, would write from Washington that “the film was destined to rot slowly in the archives as an official congressional document.”

He wasn’t wrong about that. The film was mostly rejected, propaganda many theater owners said. But the movie’s failure at the box office didn’t bury director Pare Lorentz. Lorentz was a new dealer through-and-through. He was often called “FDR’s film maker.”

Lorentz would go on to direct two other classic propaganda films for the government: "The River", about the Tennessee Valley Authority and "The Fight for Life", about infant mortality in America. Lorentz died in 1992 at age 86, but his career as documentarian isn’t forgotten. Young film makers are trained at the Pare Lorentz Institute at the FDR Library.

Virgil Thompson, who wrote the score, grew up in Kansas City but he spent his career in New York. He was a friend of Gertrud Stein and a peer of Aaron Copeland. Thompson would also work with Lorentz on The River. And in one more little connection to Kansas, that score was used in the 1983 movie The Day After, a film about nuclear war shot in Lawrence. Thompson died in 1989 at age 92.

Our theme music is used in this episode is Shy Touches by Nameless Dancers. Other music used in this episode is Snowcrop and A Rush of Clear Water by Blue Dot Sessions; both have been edited.